This panel, which I organized, was composed of myself, Dr. Margaret LaWare, Ruben Aguirre, and Miguel Aguilar, educators and artists who have been involved in Pilsen in varying capacities for many years. In this conversation, which I will summarize, the participants revealed a nuanced understanding of the transformations effecting public art in Pilsen, as well as the various misappropriations taking place and difficulties facing the neighborhood.

I opened by discussing the overall question for the panel, which was, how to negotiate the prevalence of "creative cities" discourse, Richard Florida's claim that is increasingly used to gentrify, commodify, and to monetize creative cultures, alongside with claims, in Henri Lefebvre's terms, for the "right to the city," a claim that is often supported and expressed via public art. In Pilsen, a primarily Mexican-American neighborhood on Chicago's south west side, these two trajectories are have been incredibly intense, and in tension, particularly between the 1970s and the present.

I suggested a shift in style, away from social realist, representational aesthetics, to more abstract, less polemical, and less figurative approaches to publics works (a tendency that was largely supported by narratives from co-panelists), before turning it over to the other panelists.

Ruben began with Mario Castillo's 1969s work, Wall of Brotherhood, which is no longer in existence. "Pilsen has a long history of murals, all temporary. Many don't exist anymore: they are run down, painted over, or faded." He pointed to a "collision" that often takes place between art and community dialogue, and commodification of Pilsen, and then the question "How do you see things as an artist and as a non artist?" He answered this question obliquely, pointing to both the importance of the art work's temporality, as well as some of the changing purposes and needs that art making fulfills, which are historically specific.

|

| Mario Castillo. "Wall of Brotherhood." Image courtesy of Ruben Aguirre |

Ruben also marked a historical shift in the role that public art, specifically, muralism, plays in the neighborhood. It began as a kind of means for galvanizing street protests and speaking out to people. It is linked to the 1960s and 1970s civil rights movements. But as time went on, and the neighborhood changed, the "children of that era" begin "Playing with graffiti...its a reflection of the next generation" and yet, Ruben remarked, it often involves a kind of loss of this history, a lack of memory, and no direct link with the people who came before, particularly, one might imagine, with the kind of plop art street art model. What is lost is the kind of "blunt resistance."

Ruben's own work, explores some of these histories and connections, looking for ways to engage organically with the site of inscription.

|

| Ruben Aguirre. Mural on side of Simones in Pilsen. 2013. Photo courtesy of Ruben Aguirre. |

|

| Casa Aztlán. Pilsen, Chicago. Online. |

|

| Hector Duarte. "Gulliver en el pais de maravillas." Gulliver in wonderland. Pilsen, Chicago. Online. |

|

| Kane 1. 2109 S. Ashland. Photo from Chicago Arts & Culture Online. |

Miguel sketched a similar trajectory in Pilsen's art making from the 1960s to the present. He noted that most of the muralism there was formulated with the idea of "art as community dialogue," and he featured Hector Duarte's "Gulliver's Travel's" mural. These initial murals somewhat calcified the genre of public art in the neighborhood, generating "finite parameters around what Pilsen celebration of heritage murals" might look like. They usually are "working class, religious, about education, or youth represented from the perspective of adults." This static format was problematic, he argued, because it "removes agency from the hybrid experience of Mexican American generations that are having a really different experience" than that of their predecessors. He grew up a block from Casa Azltán, the center Maggie discusses in her 1998 piece. In the 1980s and the 1990s many of his generation "feel a huge distance...they have an American educational upbringing and [the images represented in the mural are of] a time far away."

|

| "Declaration of Immigration." Image from Erinn Felix. |

In 1989 Miguel got involved with graffiti, it was illegal, and he was thirteen or fourteen. He did not "have the modeled mobility to know [that one could] work with a real estate developer to get permission" and instead "found neglected spaces," and later "learned that there are modes of operating within authoritative capacities, and built a personal relationship with private real estate owners that would let him carry out work if we would 1) curate the wall, 2) cover it through out of pocket expenses, 3) and not receive any compensation for work." Graffiti here, similar to Ruben's narrative, emerges as a means for youth that come after the generation of the 1960s/1970s to express themselves in urban spaces, and yet, it is a mode of production that carries intense risk without the "modeled mobility" that teaches them to work within existing property regimes. Graffiti is a global movement, but fulfills local and specific needs for its practitioners in Chicago. He powerfully observed:

Graffiti is a coded visual language that is closed off, has an inward community, and has a political disposition. Anonymity and secret bodies of knowledge have implications for survival, for agency, for mobilization.

However, it is becoming increasingly less "inward" and the visual cultures are blurred. In Pilsen, he notices a lot of "schoolbus tours from Evanston to visit taquerias and bakeries, and the National Museum of Mexican Art." When youth have short breaks before they reboard their buses they will often bust tags, and these tags, from the suburbs, are often later read as evidence of "ghetto" or inner city youth activity, because they have the formal elements that Chicago Police have on file for "gang signs."

Moreover, other outward pressure comes in the form of commission work for international artists. The Alderman's Art in Public Places initiative supported a visit from ROA, a Belgian street artist, well known for his enormous pieces of animals. The artist was already in town for Lollapalooza music festival.

| ROA. 16th Street Viaduct, Chicago. Photo from the Redeye. |

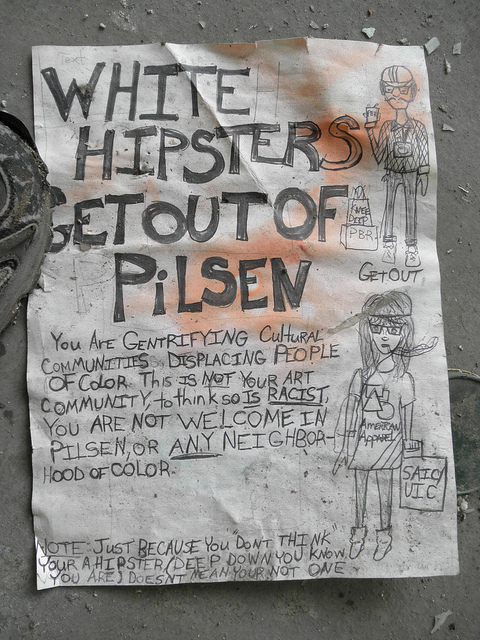

Other signs of resistance to gentrification dynamics are evident in the "White Hipsters Get Out of Pilsen," posters that can be found pasted to light poles, which names SAIC and UIC as responsible parties in the gentrification of the neighborhood, which, Miguel suggested, is driven around "hegemony, and dominant discourses, and the white gaze" which leaves "no potential for ...wild thoughts and counterknowledge" which would question "how valid it is to cast a value system of something economic over another peoples' space and culture," a concern bell hooks has also raised. There is also general frustration about how there is a "ton of unnoticed public space that was used by artists that has received new interest by politicians for a tourism agenda." Another public project that has caused some frustration on the part of graffiti artists was JR's Inside Out Pilsen installation, which was tagged over by Reken with the phrase "get in where you fit in", pointing to the fact that it required an artist from outside of Chicago to call attention to Pilsen.

|

| JR Inside Out Pilsen. |

Another theme that emerged was the idea that the murals from the 1960s to 1970s retrospectively functioned somewhat like monuments, remaining as exemplary references to an idealized group identity, even if at their time of installation they were dynamic sites for ongoing conversations. Gallagher noted, implicitly cautioning against reading monuments as a-temporal: "there is an out-loudness to monumentality...like in Andy Goldsworthy's work, an awareness of the passage of time, a playfulness.

Graffiti, is ephemeral, perhaps monumental is size, but not permanent in duration. This, Miguel explained, has a lot to do with the conditions of material scarcity that writers in spaces like Pilsen encounter. He noted: "Because of the lack of space in graffiti communities of practice going over owns own work was common, and walls rotate. There is impermanence. Not longing to have work up for decades. This is different from the history of significant representational work in spaces like museums, where there are pedestal walls. [Graffiti instead is for] rapid digestion, dispensable, and you don't need to remember." Moreover, he noted "there is an internal gratification to the process. The experience as the maker matters. It can be cathartic for people with no voice from marginalized communities. This non confrontational release is beneficial for the producers."

Dr. TR Morris asked the writers if they felt sad when their work is gone over. Ruben responded: "I don't get attached to the work, and that it can be erased immediate is good, it makes me more humble. The experience of doing it is powerful, and it is different than studio painting. [In the studio] I can reflect inwardly and it is quiet. Painting outside, being outside, there are people walking by, it can be raining, it can be really, really hot...there is a physical challenge...that is rewarding. It is challenging creatively and physically." Dr. Lester Olson pointed out that this language of physicality of painting also was prevalent in Diego Rivera's work in the 1920s to the 1950s.

Miguel also challenged the common misconception that "graffiti is individual and murals are collective." He explained: "there is a lot of collaboration in graffiti, about color choices, placement, theme." I suggested that the questioner attend a Meeting of Styles in Chicago to see these practices live.

The discussion was informative, bringing the nuance and detail of decades of study, practice, and investment in Chicago's public spaces to understand some of the less talked about dynamics of art as a practice of spatial expression and communal ownership, and art as an appropriated element of gentrification, and both art and gentrification as complex, multidimensional processes. Such conversations are only possible when we combine scholarship alongside the concrete and grounded practices of artists who are living the very processes we seek to understand. I want to thank Margaret, Miguel, and Ruben for joining me in Chicago to further texture our understanding of the intersection between public art, urban citizenship and the increasing commodification of the city as well as urban visual cultures.

You can find more of Miguel's Graffiti Institute and personal work here, Ruben's work here, and Maggie's work here.